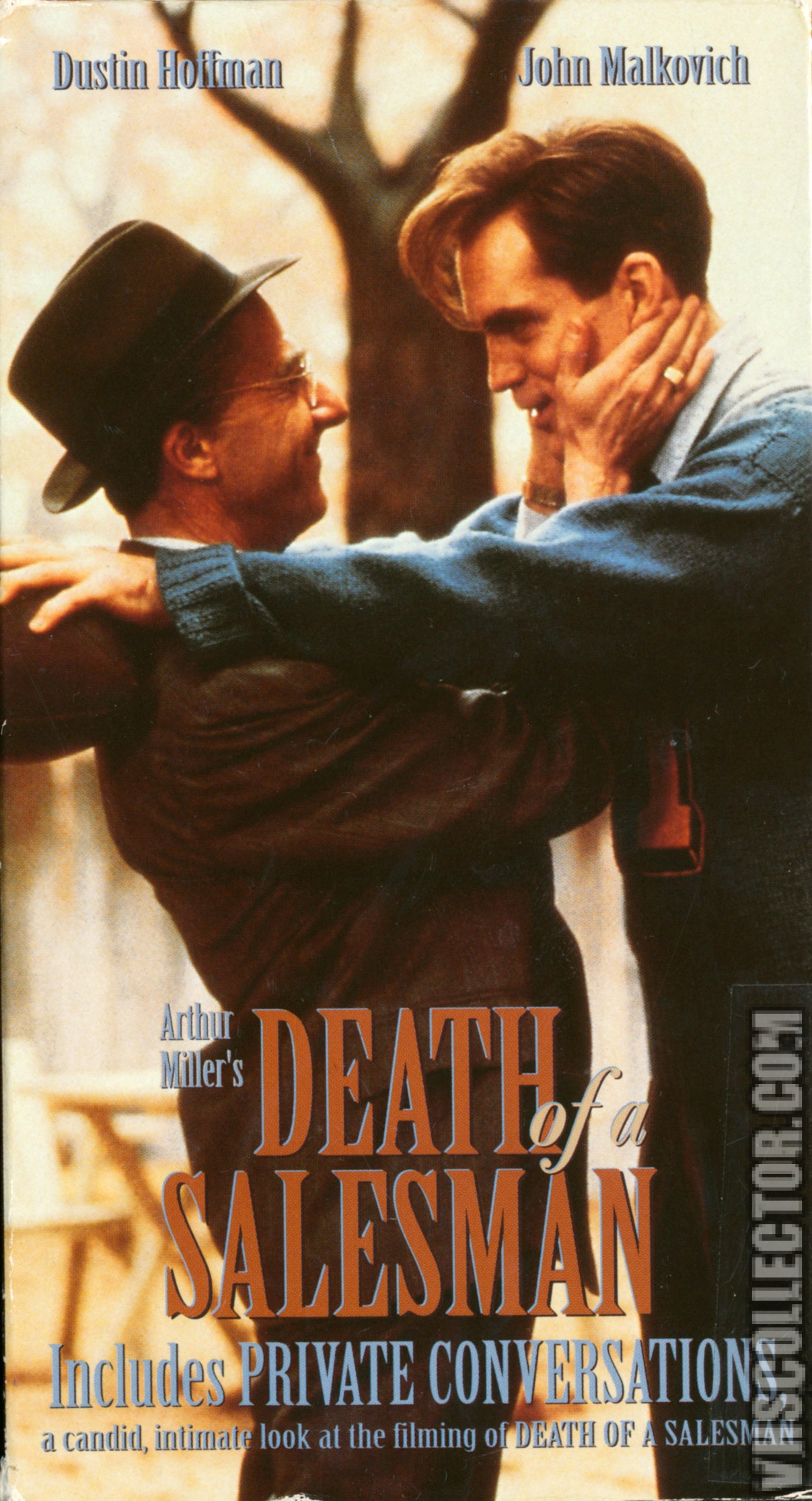

Like many people, I first encountered “Salesman” as a teen-ager, and-as with Steinbeck or Harper Lee-it was encouraging to discover that a supposed masterpiece of American literature could be so direct, comprehensible, and unmissably poignant. What I found so disappointing wasn’t the new production, however: it was the play itself. Philip Seymour Hoffman is magnificent as Willy Loman, the unspooling protagonist who, after decades of hard work, realizes (and is destroyed by the realization) that he has built his life on sand how much strain and disappointment, how much stooped, shuffling anguish Hoffman is able to communicate simply by walking from one side of the stage to the other! Linda Emond, who plays Willy’s fretful wife, Linda, along with Andrew Garfield (their wayward, chronically underachieving elder son, Biff) and Finn Wittrock (Biff’s younger, better-adjusted brother, Happy), all do the work for which Miller intended them, enhancing and complicating the spectacle of a patriarch’s demise. The new production, directed by Mike Nichols, has been lavishly praised, and it would be miserly to suggest that none of this praise is warranted. I thought of this class recently, when I went to see Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman,” currently in revival at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre, in New York. Goodnight,” or “She approached me / About buying her desk,” or “Books are a load of crap.” In other words, the best poems are often those that prompt the response: “ That doesn’t sound like poetry.” (“When was the last time anyone here saw a bower?” he asked flatly.) The best poetry, our teacher was trying to get us to realize, was that which smuggled into verse things that you would never expect to find there-like the lines, “Goodnight Bill. What our teacher was complaining about, it now seems obvious, was the tendency of students to cloak our rather banal thoughts and impressions in a poetical gauze-our tendency, after reading Keats, say, to fill our poems with bowers and nightingales and long, slow vowels. I once had a creative-writing teacher who would tactfully condemn a line of student verse by saying, in the long-suffering yet indulgent tone with which a wife might scold her husband for once again forgetting to put the cat out, “It sounds like poetry.” Sometimes, to mix things up-there was much to criticize in our work-he would put it another way: “This sounds like the kind of thing you might find in a poem.” Why this should have been such a defect was not entirely clear to us at the time.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)